The Arabic language is a semantic language with a complicated morphology, which is significantly different from the most popular languages, such as English, Spanish, French, and Chinese. Arabic is an official language in over 22 countries. It is spoken as first language in North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Sudan), the Arabian Peninsula (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen), Middle East (Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria), and other Arab countries (Mauritania, Comoros, Djibouti, Somalia). Since Arabic is the language of the Quran, the holy book of Islam, it is also spoken as a second language by several Asian countries such as: Indonesia, Pakistan, Iran, Uzbekistan and Malay[52]. More than 422 million people are able to speak Arabic, which makes this language the fifth most spoken language in the world, according to[53].

This chapter give brief description about the relevant basic elements of the Arabic language. This covers Arabic language structure, and the features of the Arabic writing system. The morphology of Arabic language and the Arabic word classes, i. e. nouns, verbs, and particles are presented in this chapter. The Arabic language challenges are also discussed in the last section of this chapter.

The Arabic language is classified into three forms: Classical Arabic (CA), Colloquial Arabic Dialects (CAD), and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). CA is fully vowelized and includes classical historical liturgical text and old literature texts. CAD includes predominantly spoken vernaculars, and each Arab country has its dialect. MSA is the official language and includes news, media, and official documents[16]. The direction of writing in the Arabic language is from right to left. The alphabet of the Arabic language consists of 28 as shown in Table 2-1.

Table 2‑1: The alphabet of the Arabic language

|

No. |

Alone Form |

Transliteration |

Initial Form |

Medial Form |

End Form |

|

1 |

ا |

a |

ا |

ـا |

ـا |

|

2 |

ب |

b |

بـ |

ـبـ |

ـب |

|

3 |

ت |

t |

تـ |

ـتـ |

ـت |

|

4 |

Ø« |

th |

ثـ |

ـثـ |

ـث |

|

5 |

ج |

j |

جـ |

ـجـ |

ـج |

|

6 |

Ø |

h |

ØÙ€ |

Ù€ØÙ€ |

Ù€Ø |

|

7 |

Ø® |

kh |

خـ |

ـخـ |

ـخ |

|

8 |

د |

d |

د |

ـد |

ـد |

|

9 |

Ø° |

th |

Ø° |

ـذ |

ـذ |

|

10 |

ر |

r |

ر |

ـر |

ـر |

|

11 |

ز |

z |

ز |

ـز |

ـز |

|

12 |

س |

s |

سـ |

ـسـ |

ـس |

|

13 |

Ø´ |

sh |

شـ |

ـشـ |

ـش |

|

14 |

ص |

s |

صـ |

ـصـ |

ـص |

|

15 |

ض |

tha |

ضـ |

ـضـ |

ـض |

|

16 |

Ø· |

ta |

طـ |

ـطـ |

ـط |

|

17 |

ظ |

tha |

ظـ |

ـظـ |

ـظ |

|

18 |

ع |

a’a |

عـ |

ـعـ |

ـع |

|

19 |

غ |

gh |

غـ |

ـغـ |

ـغ |

|

20 |

Ù |

f |

ÙÙ€ |

Ù€ÙÙ€ |

Ù€Ù |

|

21 |

Ù‚ |

q |

قـ |

ـقـ |

ـق |

|

22 |

Ùƒ |

k |

كـ |

ـكـ |

ـك |

|

23 |

Ù„ |

l |

لـ |

ـلـ |

ـل |

|

24 |

Ù… |

m |

مـ |

ـمـ |

ـم |

|

25 |

Ù† |

n |

نـ |

ـنـ |

ـن |

|

26 |

هـ |

h |

هـ |

ـهـ |

ـه |

|

27 |

Ùˆ |

w |

Ùˆ |

ـو |

ـو |

|

28 |

ÙŠ |

y |

يـ |

ـيـ |

ـي |

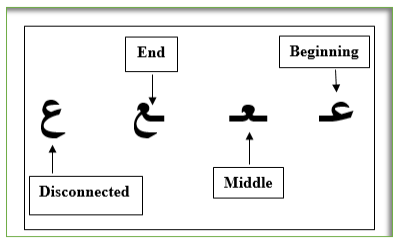

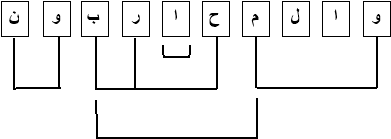

The formulation and shape are different for the same letter, depending on its position within the word [24]. For example, the letter (ع) has the following styles: (عـ),

if this letter appears at the beginning of the word, such as in عام that means general; (ـعـ), if this letter appears in the middle of the word, such as in يعر٠that means know; (ـع), if this letter appears at the end of the word, such as in يسمع that means hear. Finally, the letter (ع) can appear as (ع) if this letter appears at the end of a word but disconnected from the letter before it such as in سرع that means fast see Figure (2-1).

Figure 2-1: The Formulation and Shape for the Same Letter

Thus, a three-letter word may start with a letter in beginning form, followed by a letter in medial form and, finally, by a letter in an end form such as:

[عمل]

Instead of:

[ع م ل]

But the reality is even worse since a letter, in the middle of a word, may have the final or the initial form as in

[Ùرس]

Because some letters do not connect with any character that comes after. They have only two forms: isolated (which is also used as initial) and final (also used as middle). These letters are (د، ذ، ر، ز، و) for example:

[وردة]

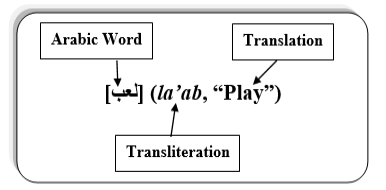

For the purpose of this thesis, we have defined our own transliteration scheme for Arabic alphabets, which is presented in Table 2.1. Each Arabic letter in this scheme is mapped to only one English letter. Wherever in this thesis, any Arabic word is annotated as a triple attribute to be more clear for a non-Arabic reader. The first attribute for the Arabic word itself which is written in Arabic scripts between two square brackets, the second attribute for an English transliteration which is written in italics, while the third one for English translation which is written between two quotation marks. Figure 2-2 shows an example.

Figure 2-2: An Example of Annotated Arabic Word

Three letters from the twenty-eight letters appear in different shapes, which are they:

The above three letters pose some difficulties when building morphological systems. Many of the written Arabic texts and Arabic web sites ignore the Hamza and the two dots above the Taa-Marbuta. For example, the Arabic word [مدرسة] (mdrst, “school”) may appear in many texts as [مدرسه] (mdrsh) (which means “school” or “his teacher”) without two dots above the last letter. When comparing the last letter in the two previous words, we found it was [Ø©] in the first word, while it was [هـ] in the second word.

Twenty-five of Arabic alphabets represent consonants. The remaining three letters represent the weak letters or the long vowels of Arabic (shortly vowels). These letters are: Alef[ا], Waaw[و] and Yaa[ي].

Moreover, diacritics are used in the Arabic language, which are symbols placed above or below the letters to add distinct pronunciation, grammatical formulation, and sometimes another meaning to the whole word. Arabic diacritics include, dama (Ù), fathah (ÙŽ), kasra (Ù), sukon (Ù’), double dama (ÙŒ), double fathah (Ù‹), double kasra (Ù) [54]. For instance, Table 2-2 presents different pronunciations of the letter (Sad) ((ص:

Table 2‑2: Presents different pronunciations of the letter (Sad) (ص)

|

صْ |

صٌ |

ص٠|

صً |

ص٠|

صَ |

ص٠|

|

/s/ |

/sun/ |

/sin/ |

/san/ |

/si/ |

/sa/ |

/su/ |

In addition, Arabic has special mark rather than the previous diacritics. this mark is called gemination mark (shaddah (شدة) or tashdeed). Gemination is a mark written above the letter (ـّ) to indicate a doubled consonant while pronouncing it. This is done when the first consonant has the null diacritical mark skoon (ـْ), and the second consonant has any other diacritical mark. For example, in the Arabic word (كسْسَر) (kssr, “he smashed to pieces”), when the first syllable ends with (س)(s) and the next starts with (س) (s), the two consonants are united and the gemination mark indicates this union. So, the previous word is written as (كسّر), and it has four letters {Ùƒ س س ر}[55].

The Arabic language has two genders, feminine (مؤنث) and masculine (مذكر); three numbers, singular (Ù…Ùرد), dual (مثنى), and plural (جمع); and three grammatical cases, nominative (الرÙع), accusative (النصب), and genitive (الجر). In general, Arabic words are categorized as particles (ادوات), nouns (اسماء), or verbs (اÙعال). Nouns in Arabic including adjectives (صÙات) and adverbs (ظروÙ) and can be derived from other nouns, verbs, or particles. Nouns in the Arabic language cover proper nouns (such as people, places, things, ideas, day and month names, etc.). A noun has the nominative case when it is the subject (Ùاعل); accusative when it is the object of a verb (Ù…Ùعول) and the genitive when it is the object of a preposition (مجرور بØر٠جر) [56]. Verbs in Arabic are divided into perfect (صيغة الÙعل التام), imperfect (صيغة ال٠الناقص) and imperative (صيغة الامر). Arabic particle category includes pronouns(الضمائر), adjectives(الصÙات), adverbs(الاØوال), conjunctions(العطÙ), prepositions (Øرو٠الجر), interjections (صيغة التعجب) and interrogatives (علامات الاستÙهام) [57].

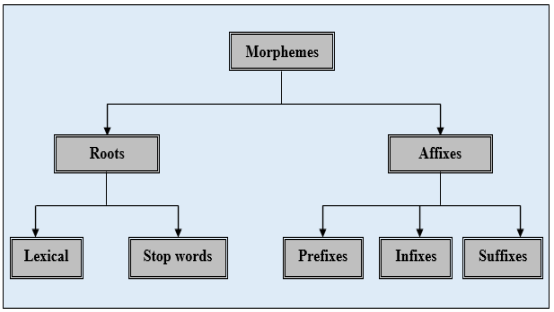

The Arabic language is one of the highly sophisticated natural languages which has a very rich and complicated morphology. Morphology’ is the part of linguistics that deal with the internal structure and formation processes of words. A morpheme is often defined as the smallest meaningful and significant unit of language, which cannot be broken down into smaller parts[58]. So, for example, the word apple consists of a single morpheme (the morpheme apple), while the word apples consist of two morphemes: the morpheme apple and the morpheme -s (indication of plural). In Arabic language for example, the word (سألهم, “he asked them”) consists also of two morphemes the verb (سأل, “he ask”) and the pronoun (هم, “them”). According to the previous examples, there are two types of morphemes: roots and affixes. The root is the main morpheme of the word, supplying the main meaning, while the affixes are added in the beginning, middle or end of the root to create new words that add additional meaning of various kinds. In more general morphemes could be classified as: (1) roots morphemes and (2) affixes morphemes, Figure 2.3 illustrated this classification.

Figure 2-3: Morpheme Classification

Root is the original morpheme of the word before any transformation processes that comprises the most important part of the word and cannot be reduced into smaller constituents. In other words, it is the primary unit of the family of the same word after removing all inflectional and derivational affixes which can stand on their own as

words (independent words). The root morphemes divided into two categories. The first category is called lexical morphemes, which covers the words in the language carrying the content of the message. Examples from English language: book, compute, and write, while examples from Arabic language: (قرأ, “read”), (لعب, “play”), and (كتب, “write”). The second category is called stop words morphemes, which covers the function words in the language. The stop words include adverbs, prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions, and prepositions. Examples from English language: on, that, the, and above. Examples from Arabic language: (ÙÙŠ, “in”), (Ùوق, “above”), and (تØت, “under”).

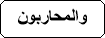

Affixes morphemes are also units of meaning; however, they cannot occur as words on their own; they need to be attached to something such as root morphemes. There are three types of affixes in Arabic language: prefixes, infixes, and suffixes. In some cases, all of these affixes can be found in one word as in the word[والمØاربون] (“and the warriors”). This word has ten letters, three of them are root-letters, while the others are affixes. The root of this word is [Øرب] (“war”). The example in Figure 2.4 can clearly deduce the differences between the three main terms used in computational linguistics: roots, stems and affixes.

Figure 2-4: The Decomposition of the Word [والمØاربون].

Arabic is a challenging language in comparison with other languages such as English for a number of reasons:

Table 2‑3: Different morphological forms of word study (درس).

|

Word |

Tense |

Pluralities |

Meaning |

Gender |

|

درس |

Past |

Single |

He studied |

Masculine |

|

درست |

Past |

Single |

She studied |

Feminine |

|

يدرس |

Present |

Single |

He studies |

Masculine |

|

تدرس |

Present |

Single |

She studied |

Feminine |

|

درسا |

Past |

Dual |

They studied |

Masculine |

|

درستا |

Past |

Dual |

They studied |

Feminine |

|

يدرسان |

Present |

Dual |

They study |

Masculine |

|

تدرسان |

Present |

Dual |

They study |

Feminine |

|

يدرسا |

Present |

Dual |

They study |

Masculine |

|

تدرسا |

Present |

Dual |

They study |

Feminine |

|

درسوا |

Past |

Plural |

They studied |

Masculine |

|

درسن |

Past |

Plural |

They studied |

Feminine |

|

تدرسن |

Present |

Plural |

They study |

Feminine |

|

سيدرس |

Future |

Single |

They will study |

Masculine |

|

ستدرس |

Future |

Single |

They will study |

Feminine |

|

سيدرسا |

Future |

Dual |

They will study |

Masculine |

|

ستدرسا |

Future |

Dual |

They will study |

Feminine |

|

سيدرسون |

Future |

Plural |

They will study |

Masculine |

|

ستدرسون |

Future |

Plural |

They will study |

Feminine |

Table 2‑4: Example: An Arabic Word could be a Complete English Sentence

|

Arabic Word |

English Sentences |

|

ذهبت |

She go |

|

سأقرأه |

I will read it |

|

سمعناه |

We hear him |

|

اخبرني |

He told me |

|

Ùغادر |

Then he departed |

Arabic language is an international language belonging to the Semitic languages family (different from Indo-European languages in some respects). The Arabic alphabet consists of twenty-eight letters in addition to some variants of existing letters. Each letter can appear in up to four different shapes, depending on the position of the letter in the Arabic word. Twenty-five of Arabic letters represent consonants. The remaining three letters represent the long vowels of Arabic. The Arabic writing system goes from right to left and most letters in Arabic words are joined together.

Arabic has a rich and complex morphology. In many cases, one orthographic word is comprising many semantic and syntactic words. Traditionally there are two types of morphology in Arabic language: roots morphemes and affixes morphemes. The root morphemes divided into two categories. The first category is called lexical morphemes, which covers the words in the language carrying the content of the message. The second category is called stop words morphemes, which covers the function words such as adverbs, prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions, and prepositions. Affixes morphemes cannot occur as words on their own; they need to be attached to something such as root morphemes. There are three types of affixes in Arabic language: prefixes, infixes, and suffixes.

All Arabic words could be classified into three main categories according to the part-of-speech: noun, verb, and particle. The noun and verb in Arabic might be further divided according to: number (singular, dual and plural), and case (nominative, genitive and accusative). Arabic. The Arabic language is a challenging language in comparison with other languages and has a complicated morphological structure. Therefore, the Arabic language needs a set of preprocessing routines to be suitable for cl